Advertisement feature

Defending the sea

In a part of the Philippines that sits within the tropical waters of the Coral Triangle, local communities are working with the Blancpain-backed Sea Academy to expand a network of conservation zones in a bid to protect and restore damaged marine ecosystems

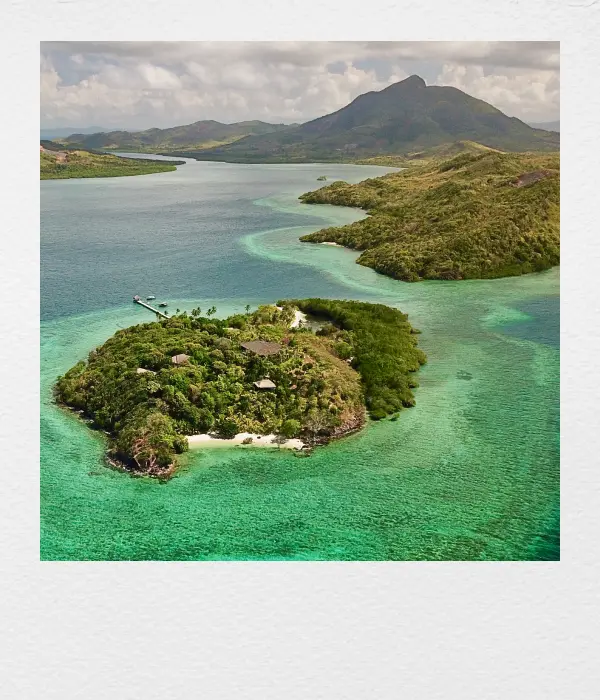

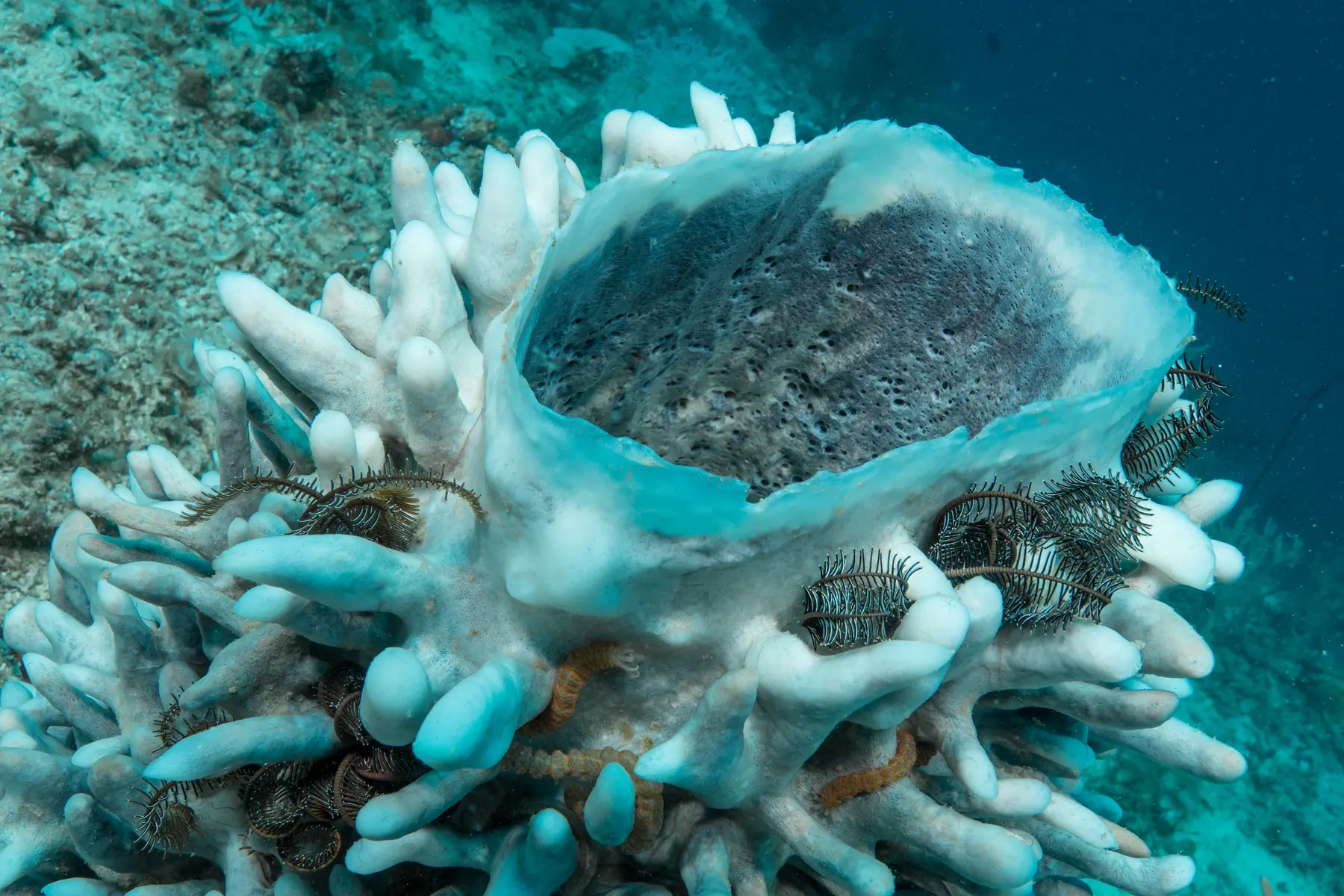

The fishermen near Pangatalan Island in the Philippines never stood a chance. Each day, they headed out with nets and hooks, hoping for a catch, only to find an empty sea. The Philippines has some of the largest coral reefs in the world, and these tropical waters once teemed with grouper and snapper. But now the reefs were dead. The fish were gone.

The culprit was dynamite, says Dante Jabelo, a 38-year-old fisherman who scratched a living from the sea. Vessels from other parts of Asia would trawl illegally, dropping explosives that killed fish indiscriminately. “It destroyed the marine life, the corals,” Mr Jabelo explains. The catch got so bad that villagers began to move away to find jobs in the city.

Now, thanks to support from an initiative called the Sea Academy, these waters are flourishing once again. Launched in 2021 by French property developer Frédéric Tardieu, with backing from Swiss watchmaker Blancpain, the academy has engaged the local community to create a network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around Pangatalan Island and the wider Shark Fin Bay where it is located, to protect the ecosystem from overfishing and restore the reefs and marine life.

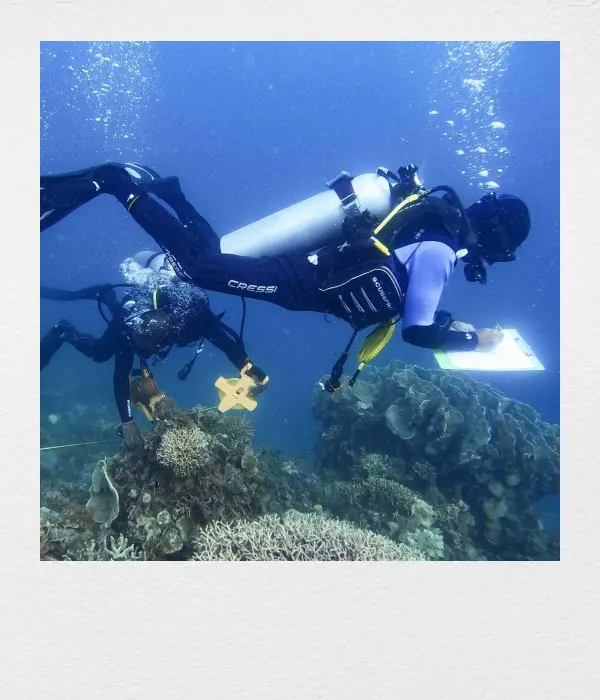

The results have been extraordinary. Species that had vanished are now thriving. These include the bulbous-headed Napoleon wrasse, the sea turtle, and the dugong, a gentle marine mammal that grazes on seagrass. As the ecosystem revives, so do the livelihoods of the local fishermen. The grouper and snapper are bigger than they have been in years, says Mr Jabelo, now a certified diver who patrols protected areas as a guard for the Sea Academy, and also catches fish in zones designated for sustainable fishing. “Me, as a fisherman, I am so happy,” he says.

However, just 7% of the world’s ocean is under some form of marine protection, according to the Marine Conservation Institute, and less than 3% of it is covered by strong enough regulations to safeguard biodiversity. Funding for ocean research and conservation work is limited. “It is just a fraction of the funds for space exploration, even though we know so little about the ocean,” says Marc Hayek, CEO of Blancpain, which has spent two decades preserving the sea through its Blancpain Ocean Commitment programme.

Starting small and engaging communities

When Mr Tardieu and his wife Chris bought Pangatalan in 2011, they immediately began to think about how to restore the damaged ecosystem. They created the Sulubaaï Environmental Foundation and established a 50-hectare protected zone around their island. An artificial reef seeded with small fragments of coral bloomed over time into a busy biosphere. With no fishing allowed in the MPA, marine life multiplied. The biomass increased threefold, and biodiversity rose by 31%. With so much wildlife, Pangatalan became a popular spot for sustainable tourism.

Critical to the success of that protected area was its relatively small size. Other MPAs can span 1,000 hectares and are harder to control, Mr Tardieu explains. His vision became bolder. He imagined a network of interconnected MPAs, protected by local communities. Each MPA would be modest in size—small enough that each village would feel a personal connection with the area in their care. “It’s very important to work at the human scale,” he says. Collectively, though, the MPAs could one day cover thousands of hectares.

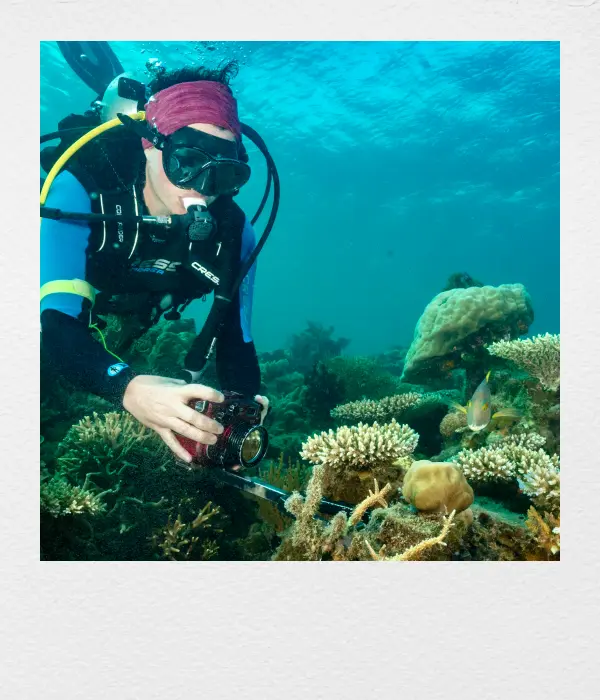

It was time to spread the word. French photographer and marine biologist Laurent Ballesta made a documentaryabout the restoration of the reef at Pangatalan, and Mr Tardieu showed the film in the villages. “I discussed MPAs in the local schools and with the governments of these villages,” he says. “I wanted to show them that the fish were coming back and were growing bigger. The idea was to engage the local population to protect their own resources.”

Photographs: © Laurent Ballesta

His persistence paid off. At public hearings, people debated creating more MPAs. Eventually, the community agreed. Three villages came on board, establishing MPAs in the waters they controlled.

A growing impact

Now, the focus is on expanding the MPAs’ reach. Supported by Blancpain, which has backed conservation programmes in ecosystems as diverse as the Russian Arctic and the South Pacific, the network of MPAs is growing as more people hear about their power to reverse environmental damage.

“The model has the advantage of fostering the development of sustainable management, with a positive and direct impact on both the environment and these communities”

Marc Hayek, CEO of Blancpain

“The model has the advantage of fostering the development of sustainable management, with a positive and direct impact on both the environment and these communities,” says Mr Hayek. Blancpain has contributed to protecting more than 4.7m sq km of ocean—an area almost twice the size of the Mediterranean Sea—he adds.

There is good momentum in the Philippines. The local municipality has agreed to set up a further 12 MPAs, a Blancpain/Sulubaaï Research Centre will open near Pangatalan this year – with space for ten marine scientists—and experts from universities in Japan, California and Europe will study the impact of the MPAs as they grow. The Sea Academy has installed 800 artificial reefs, and each year 40,000 juvenile fish are released to replenish stocks.

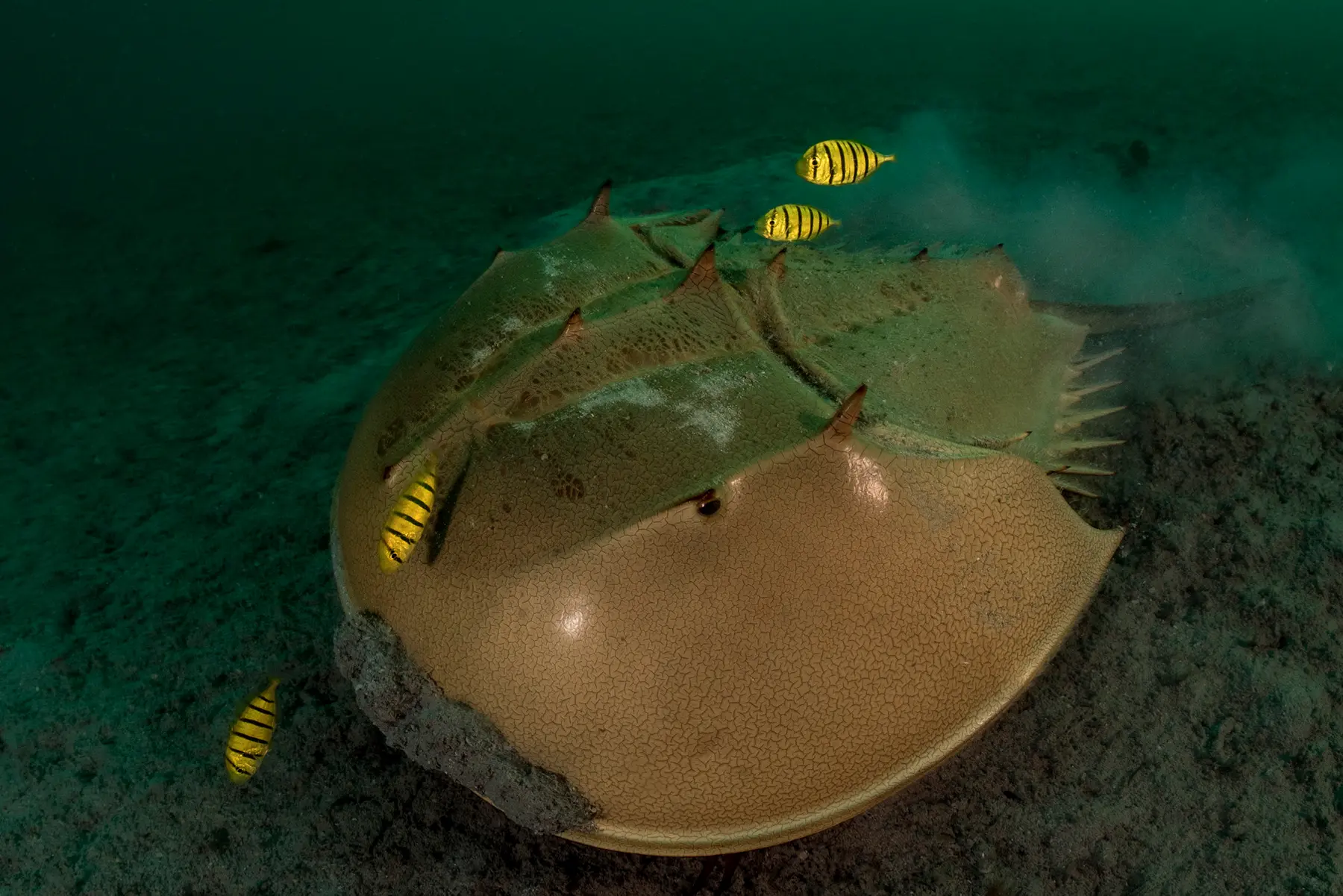

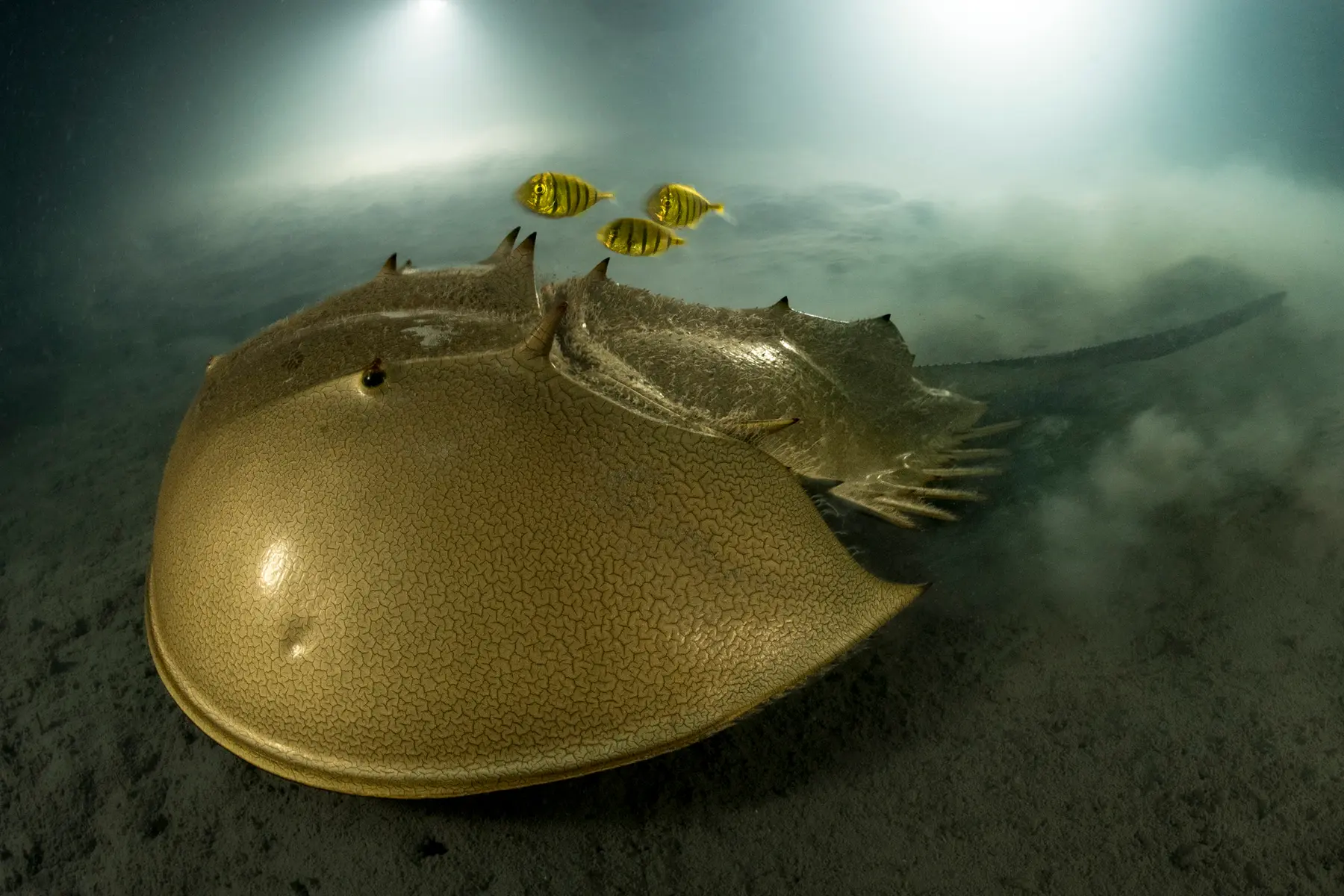

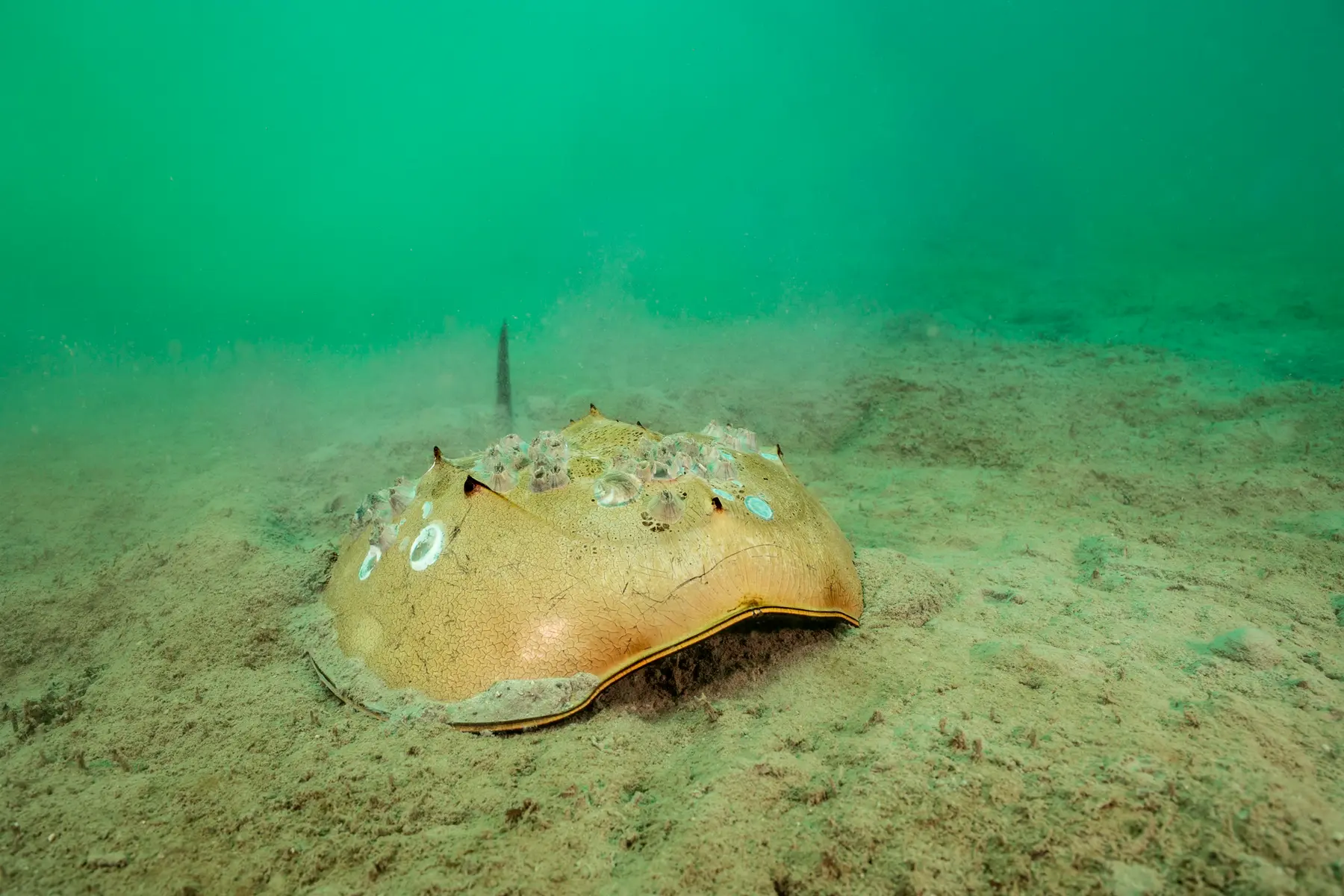

Last year, Shark Fin Bay was recognised for its exceptional ecosystem by the Marine Conservation Institute and Mr Ballesta won (for a second time) the prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, with an image captured in the waters of Pangatalan. Among the species he was helping to inventory was the horseshoe crab—a living fossil that has been around for 450m years. Unlike other horseshoe crabs, whose shells were covered in algae and scratches, he encountered a particularly striking one that was pristine. Then there was its colour. “It looked like gold,” Mr Ballesta recalls, “like a metallic shell.”

For Mr Ballesta, the purpose of the image is larger than raising awareness of the horseshoe crab through powerful photography. “If just a photo was enough to save the white rhino or the panda, it would have been done already,” he says. He is more interested in capturing a sense of mystery and wonder. “It’s a much bigger source of respect,” he explains. “If people stand in front of the picture and say, ‘Wow, is that alive? Is it from our time?’, then image by image they will come to see that biodiversity is bigger and more important than they thought.”

Photographs: © Laurent Ballesta

Produced by El Studios for Blancpain